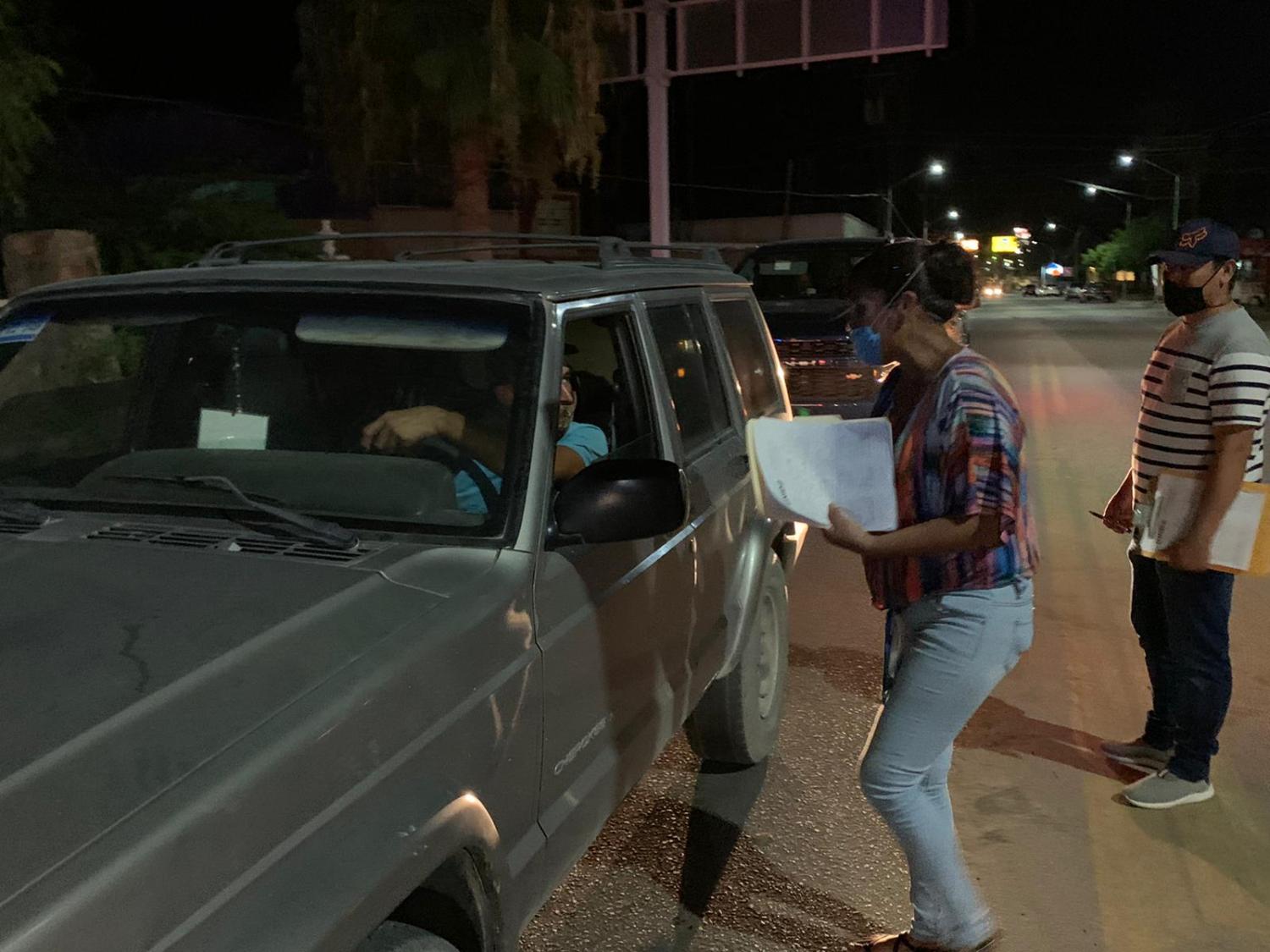

VIEW LARGER Protesters blockaded the port of entry in Sonoyta, Sonora on July 4, 2020, preventing U.S. travelers from entering their town.

VIEW LARGER Protesters blockaded the port of entry in Sonoyta, Sonora on July 4, 2020, preventing U.S. travelers from entering their town. “People during the pandemic in Sonoyta, they are scared,” said Carlos Jacquez, a 21-year-old University of Arizona student who has become an unofficial spokesperson in Sonoyta in recent weeks. “We know how horrible COVID-19 can be. And we know that people are dying in cities where they have proper hospitals that have doctors and nurses. In Sonoyta, we don’t have that.”

A border town of about 17,000 people, Sonoyta is perhaps best known to Arizonans as the town they cross through on the way to nearby Rocky Point. But local residents drew international attention over the Fourth of July weekend for rejecting those beach-bound travelers.

Protesters set up blockades outside the town’s port of entry, turning back southbound tourists hoping to spend the holiday weekend in Rocky Point.

Just days before, Sonora Gov. Claudia Pavlovich announced she was implementing travel restrictions and border checkpoints to bar nonessential travel from the United States over the holiday weekend to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19. But she later made an exception for visitors passing through Sonoyta on their way to Rocky Point.

Already struggling amid the pandemic, that was the last straw for many in Sonoyta.

Rocky Point had closed its borders to outsiders — including its neighbors in Sonoyta — early on during the pandemic to control the spread of the virus. That caused issues for Sonoytans, who couldn’t access essential services — including banks, government offices and some health care.

Now, many felt that Rocky Point’s economy had once again taken priority over Sonoyta’s health and well-being.

“Our entire town gathered together and we decided to fight for justice,” Jacquez said.

The initial border blockades came down after Rocky Point leaders quickly agreed to meet some of protesters’ demands for supplies, services and access to the nearby city. But Jacquez said the protests sparked a movement. Calling themselves Sonoyta Unido, some residents decided they were done weathering a global health crisis without basic health care.

VIEW LARGER Members of the group Sonoyta Unido gathered signatures to demand government leaders address the town's health care needs.

VIEW LARGER Members of the group Sonoyta Unido gathered signatures to demand government leaders address the town's health care needs. “We don’t have pediatrician, we don’t have specialists, we don’t have an X-Ray machine,” Jacquez said.

There’s also nowhere in town for women to give birth, added fellow Sonoyta Unido member Maritza Contreras, so women routinely travel hours to nearby cities to have their babies.

And the local health clinic in Sonoyta only has the capacity to treat the most basic symptoms of the coronavirus. To access the highest level of care means traveling up to five hours to the state capital Hermosillo.

That lack of essential services is a common problem in border cities, says researcher Rocio Barajas of Colegio de la Frontera Norte, who has been studying the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on border communities, many of which have been among the hardest hit by the virus.

“Historically, the southern border of the United States as well as the northern border of Mexico, what we call the borderlands, have been characterized by severe urban issues,” she said.

And Barajas said risk factors pile up at the border: poor air and water quality; insufficient housing; large numbers of people living in poverty, working in the informal sector and suffering from underlying conditions like diabetes and heart disease; and, of course, high cross-border mobility.

While border restrictions implemented in March have certainly impacted both families and businesses, she said, they haven’t stemmed border crossings in these inextricably connected cities. A better solution would be a coordinated, cross-border effort to distribute vital information and resources in these communities, she said.

“But it really worried me, I said, “Wow, if someone gets sick in these communities, they have to travel all the way to bigger cities for medical treatment.’ And it’s not that easy,” she said of the difficulty for residents of border cities like Sonoyta to access adequate coronavirus care.

VIEW LARGER Members of the group Sonoyta Unido spend evenings collecting signatures in town.

VIEW LARGER Members of the group Sonoyta Unido spend evenings collecting signatures in town.

“We don’t have health services in Sonoyta,” said town Mayor Jose Ramos. “We have a health clinic, but to give you an idea, we don’t have a surgery, we don’t have X-rays. It’s just, if there’s an accident or a problem, they can stabilize someone and send them to Rocky Point.”

Ramos has come under harsh criticism by protesters who don’t think he’s done enough for the community. But he said he understands why they are frustrated, because he sees the impacts of a nearly nonexistent health system, too.

People have died in Sonoyta because there aren’t enough oxygen tanks, he said. One coronavirus patient died after being rejected for care from Rocky Point, then nearby Caborca before being sent all the way to Nogales.

And while official state data show 68 coronavirus cases in the municipality as of Wednesday, Ramos says by mid-July he knew of at least 300. But a lack of information, adequate testing and access to care means many cases go undetected.

“The state government and the federal government, they’re not going to acknowledge those cases, though,” he said.

He said Sonoyta is a town at the intersection of two federal highways, a town dedicated to agriculture and cattle ranching, and a town forsaken by the government even before the pandemic.

Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador agrees.

“It’s one of Mexico’s abandoned towns,” he said during a press conference in July, when he promised to send a representative to address residents’ concerns.

That hasn’t happened yet. But Sonoyta residents aren’t giving up.

VIEW LARGER A stack of signed petitions.

VIEW LARGER A stack of signed petitions. Members of the Sonoyta Unido movement have been gathering signatures to support their demands for government leaders to attend to the town’s health care and other needs. So far, they said, nearly half the town has signed the petitions.

“I want everyone to know that we live in a society where we deserve better,: Jacquez said. “We pay our taxes, we vote for our government, we participate as citizens, but we haven’t been heard,” Jacquez said. “And I want everyone to know that we live in a society where we deserve better.”

In Sonoyta, people have been living with inadequate health care and other services for decades. But Jacquez says the pandemic tipped the scales, and now they’re finally demanding what they deserve.

“We’re hopeful. We’re really hopeful for what’s coming next,” he said.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.