The Community Medical Services clinic in Sierra Vista opened in March 2019. It serves about 130 patients and operates from 4:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.

The Community Medical Services clinic in Sierra Vista opened in March 2019. It serves about 130 patients and operates from 4:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m.

Elfrida, Arizona, is a cold and dark place at 3 a.m. in January. But it’s where Anhelica Gonzalez emerges with only a few hours’ sleep to ready her 2-year-old daughter Zarhianna for their journey to Sierra Vista.

Their MedStar ride takes them on mountain roads frequently crossed by deer and cloaked in fog. “Last time we had to wait. We had to sit on the side of the road because we couldn’t even see in front of us,” she said.

An hour later, she arrives at her destination: Community Medical Services. It’s an opioid treatment program where Gonzalez, 36, goes to get her weekly supply of methadone, which she’s using to wean herself off prescription opioid painkillers.

The clinic opened last March — the first in Cochise County to offer medication-assisted treatment. This type of treatment, previously only available in Arizona’s big cities, has expanded into rural communities in the last two years.

Increasing access to medication-assisted treatment is a pillar of the state’s strategy to combat the opioid epidemic, but distance and stigma against addiction still present barriers that keep people from getting help.

Gonzalez was prescribed oxycodone in 2008 to treat the chronic pain that comes with her degenerative disc disease. She built up a tolerance and soon she said her withdrawals made it impossible to quit.

“To feel that pain and to have to feel nauseated and not be able to move and not be able to eat anything, almost worse than the flu, and then having kids, you can’t function like that,” she said. “You can actually die from withdrawing.”

Experts consider medication-assisted treatment the “gold standard” for treating opioid addiction. It's on the World Health Organization's list of essential medicines. Research shows it’s more effective than trying to quit cold turkey. That’s because the proper dose of methadone keeps patients from going through painful withdrawal, but without the euphoric effects of illicit opioids.

Methadone is itself a synthetic opioid and has the potential for abuse. It’s highly regulated. Patients have to go to the clinic every day for up to three months before they can start to take doses home.

That requirement makes treatment in rural areas especially difficult, said Haley Horton, regional director for Community Medical Services in Southern Arizona.

“Until we opened, there was not much,” she said. “I think we would have people driving upwards of four hours a day to receive services.”

Horton has overseen the opening of clinics in Sierra Vista, Casa Grande, Nogales, Kingman and Lake Havasu City — all in the past year.

Initially buoyed by state grants, those clinics are now serving hundreds of new patients, according to data provided by Community Medical Services. Opening a clinic in smaller communities isn’t easy. They’re costly operations with staffing requirements that can’t always be met in the communities they’re entering.

Horton said getting started is a challenge, but the clinics have quickly grown into sustainable operations.

Since 2017, the state has funneled some of the $75 million it has received from the federal government to providers willing to branch out into so-called treatment deserts.

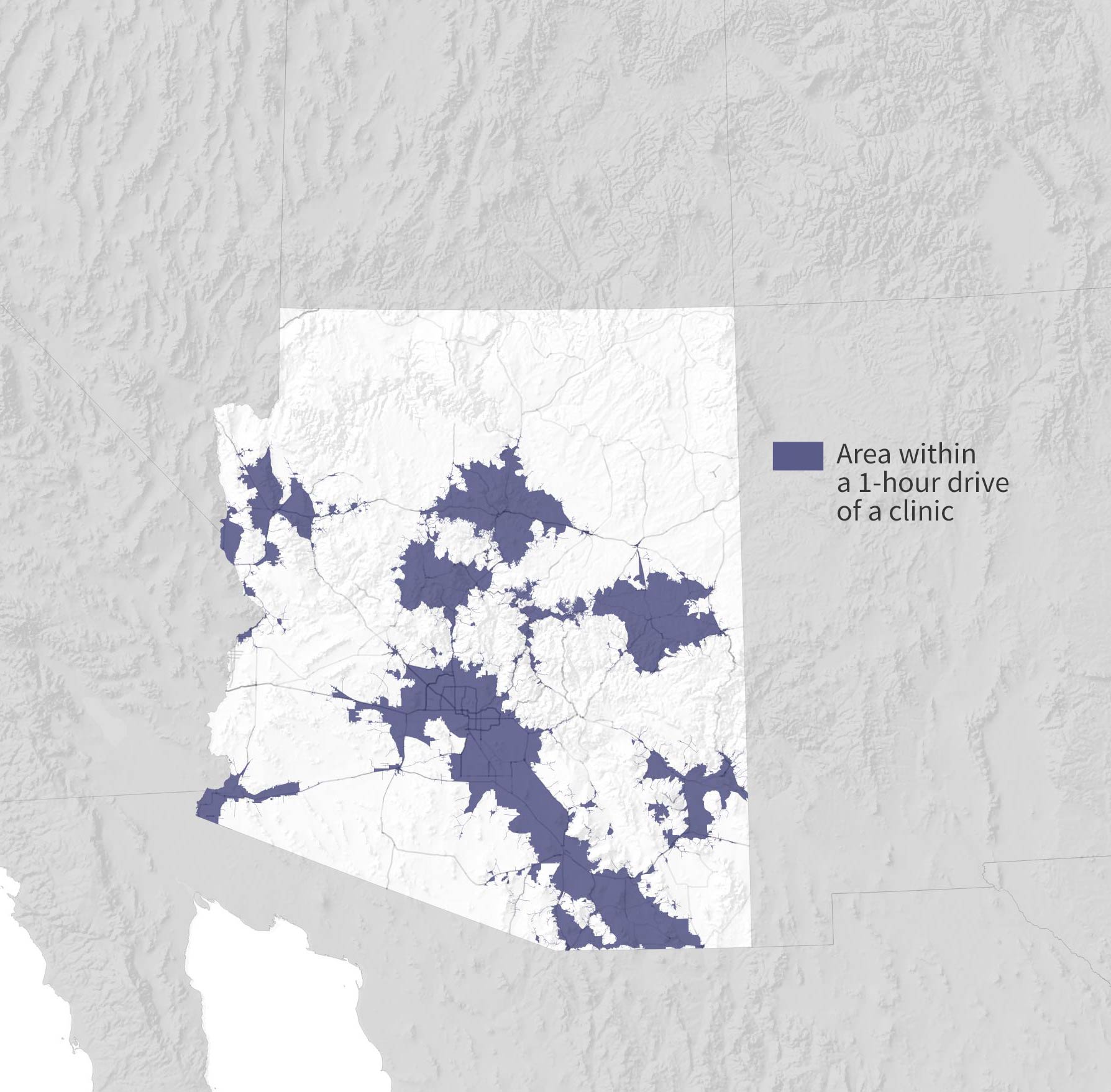

But it’s still hard to reach everybody. An Arizona Public Media analysis identified communities that are still at least an hour's drive from the nearest clinic.

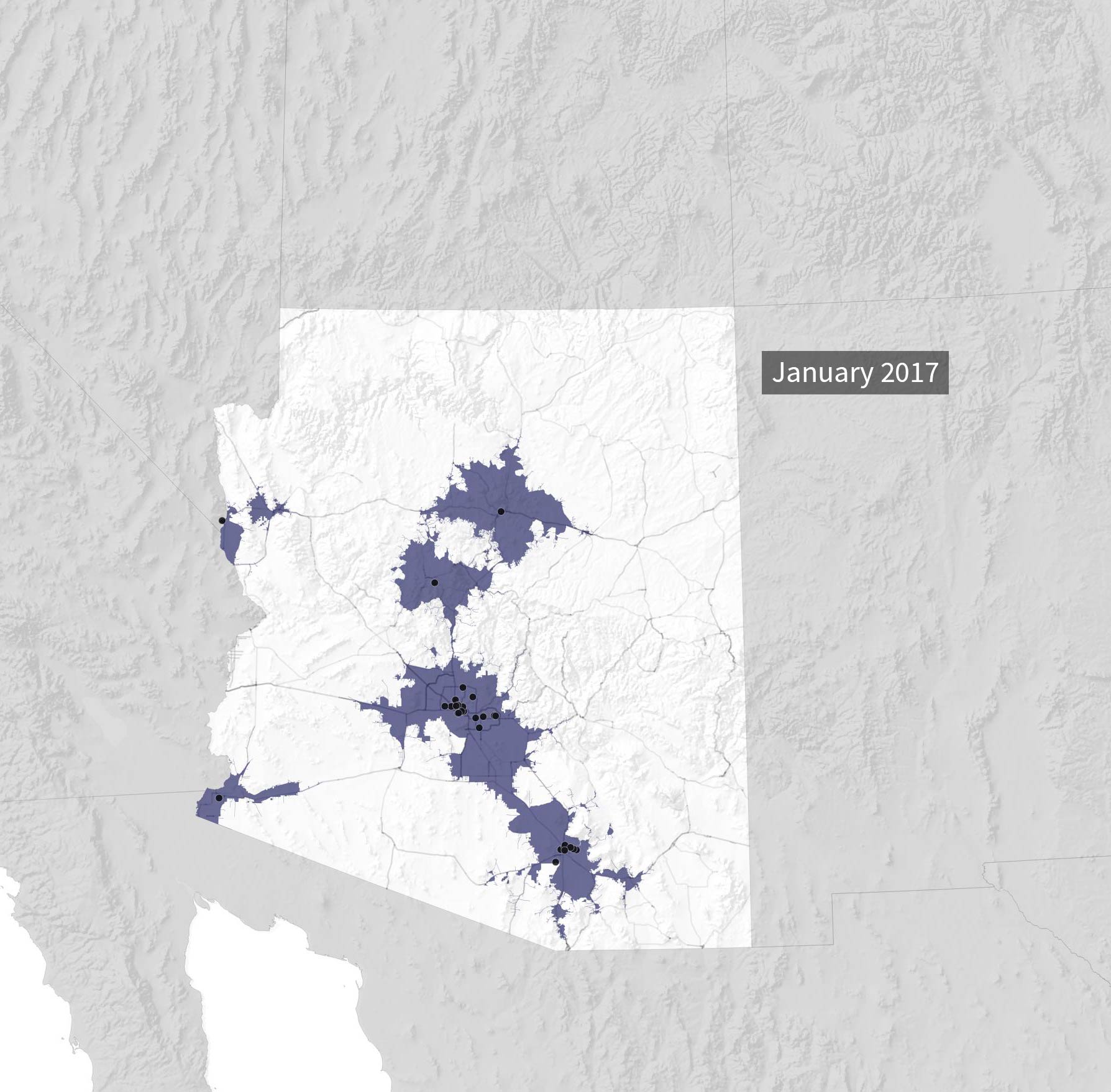

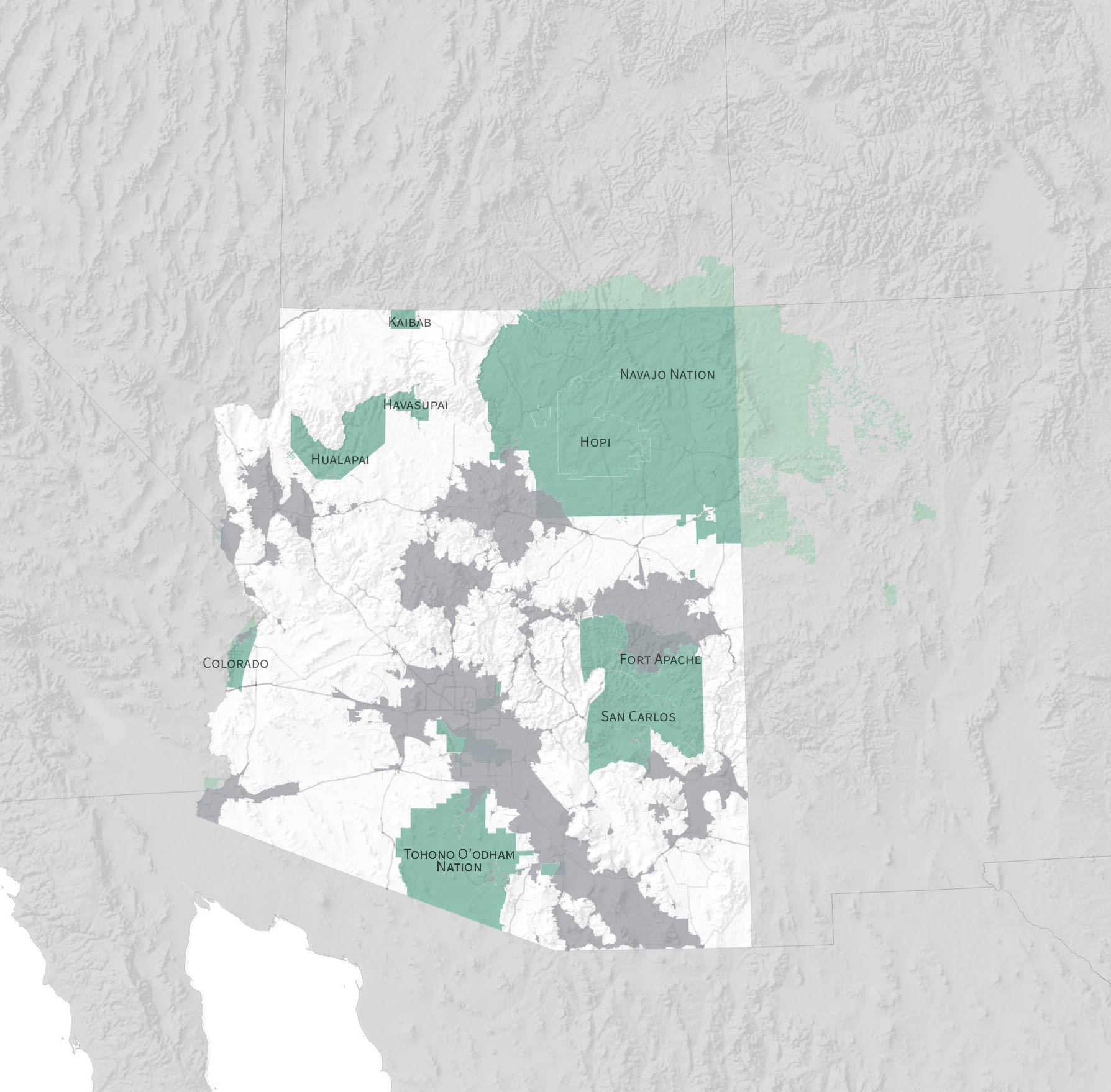

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

Before 2017, most clinics offering methadone, seen below, were in urban areas.

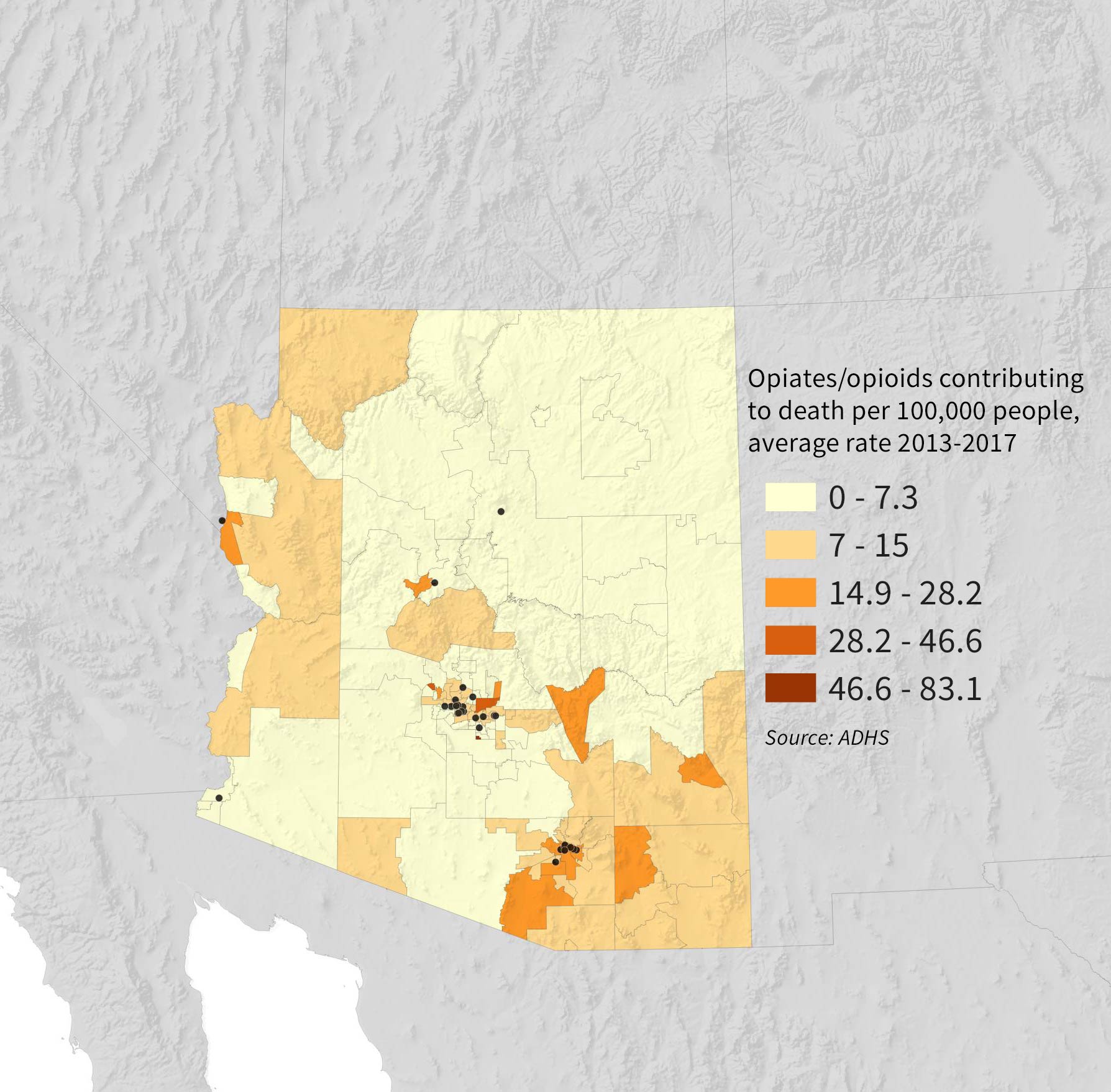

Some areas of the state hit hard by the crisis did not have a clinic.

Some areas of the state hit hard by the crisis did not have a clinic.

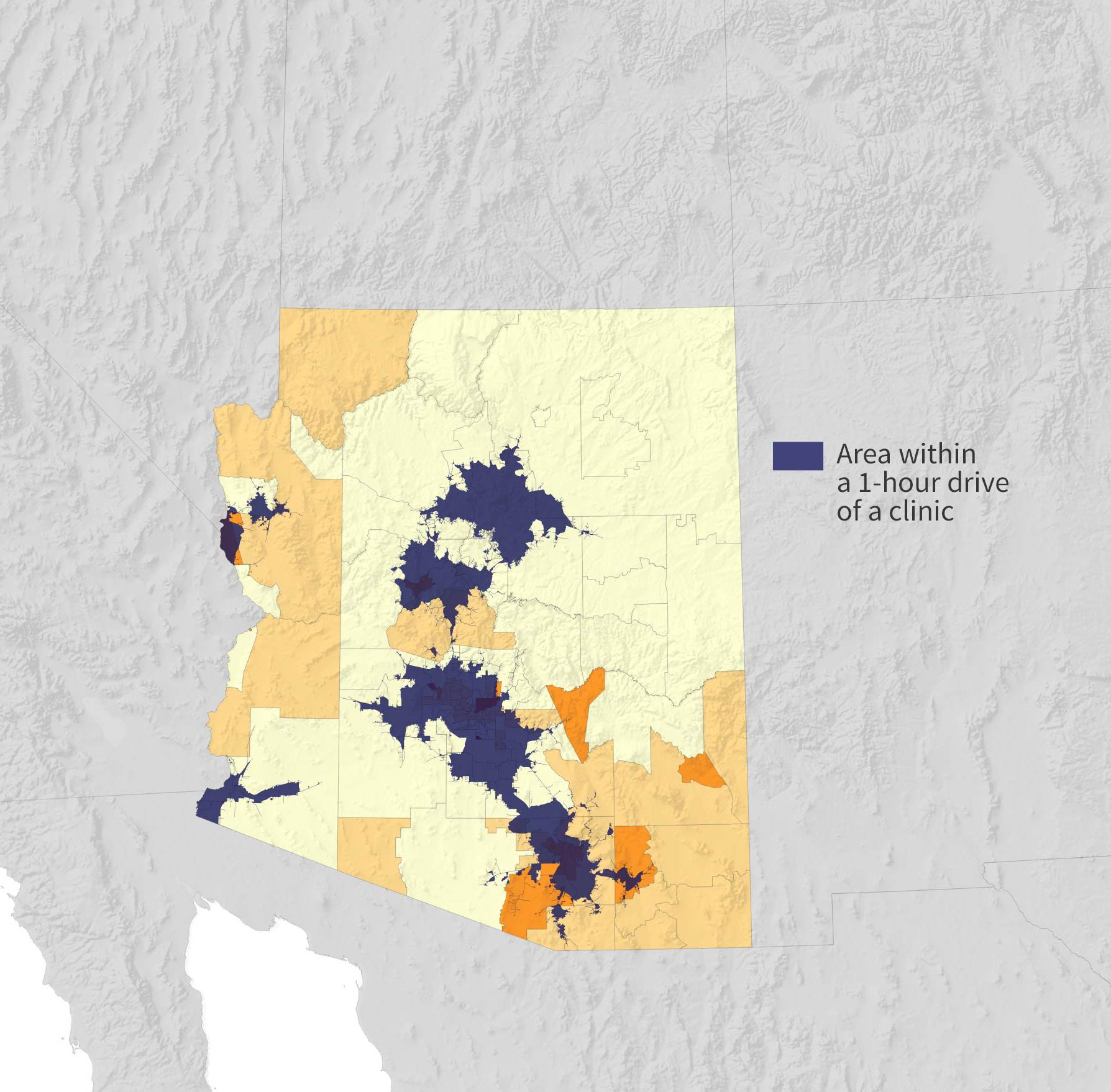

Many people in the state were more than an hour’s drive from a clinic. Treatment initially requires daily trips to receive medication.

Many people in the state were more than an hour’s drive from a clinic. Treatment initially requires daily trips to receive medication.

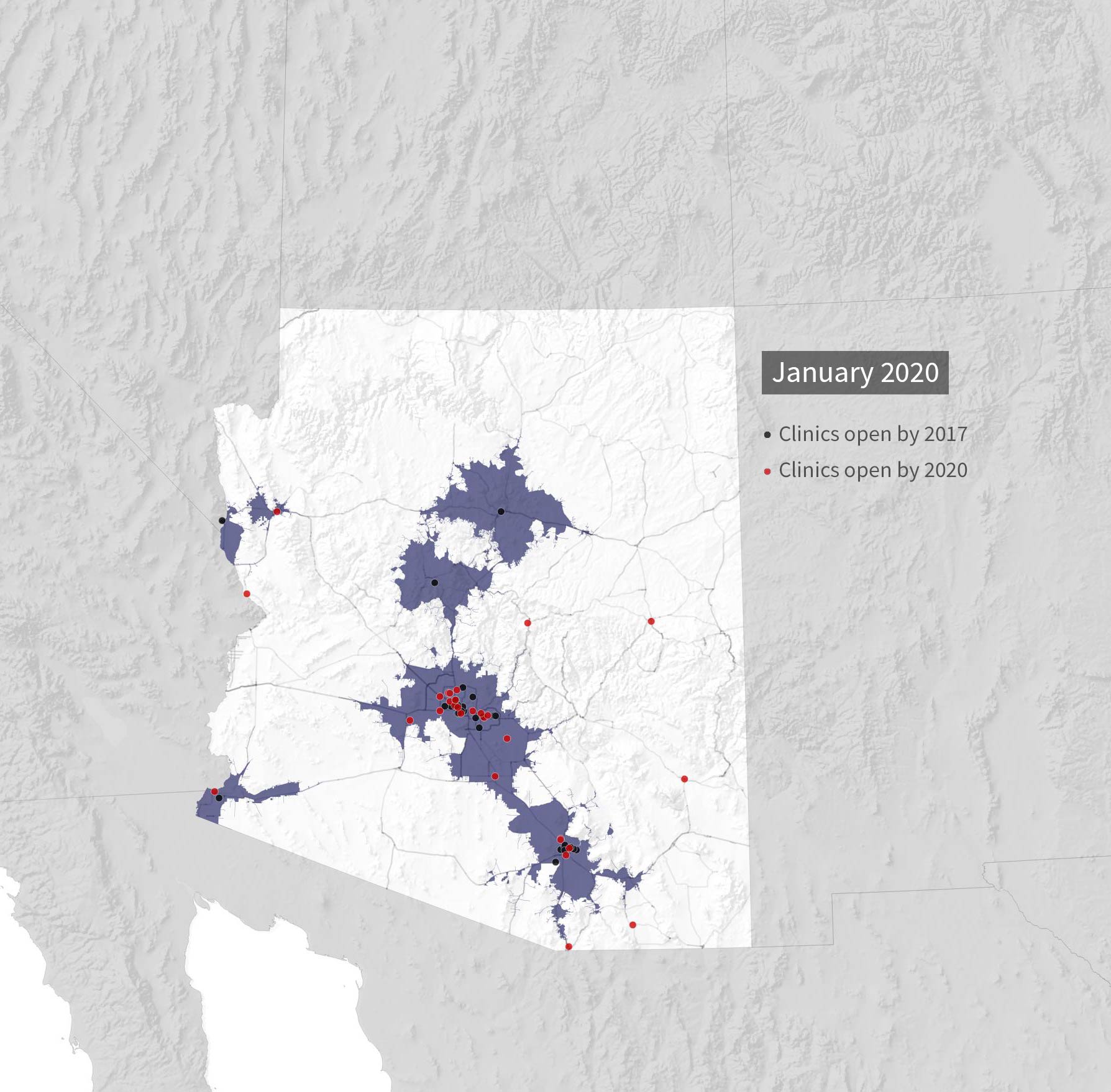

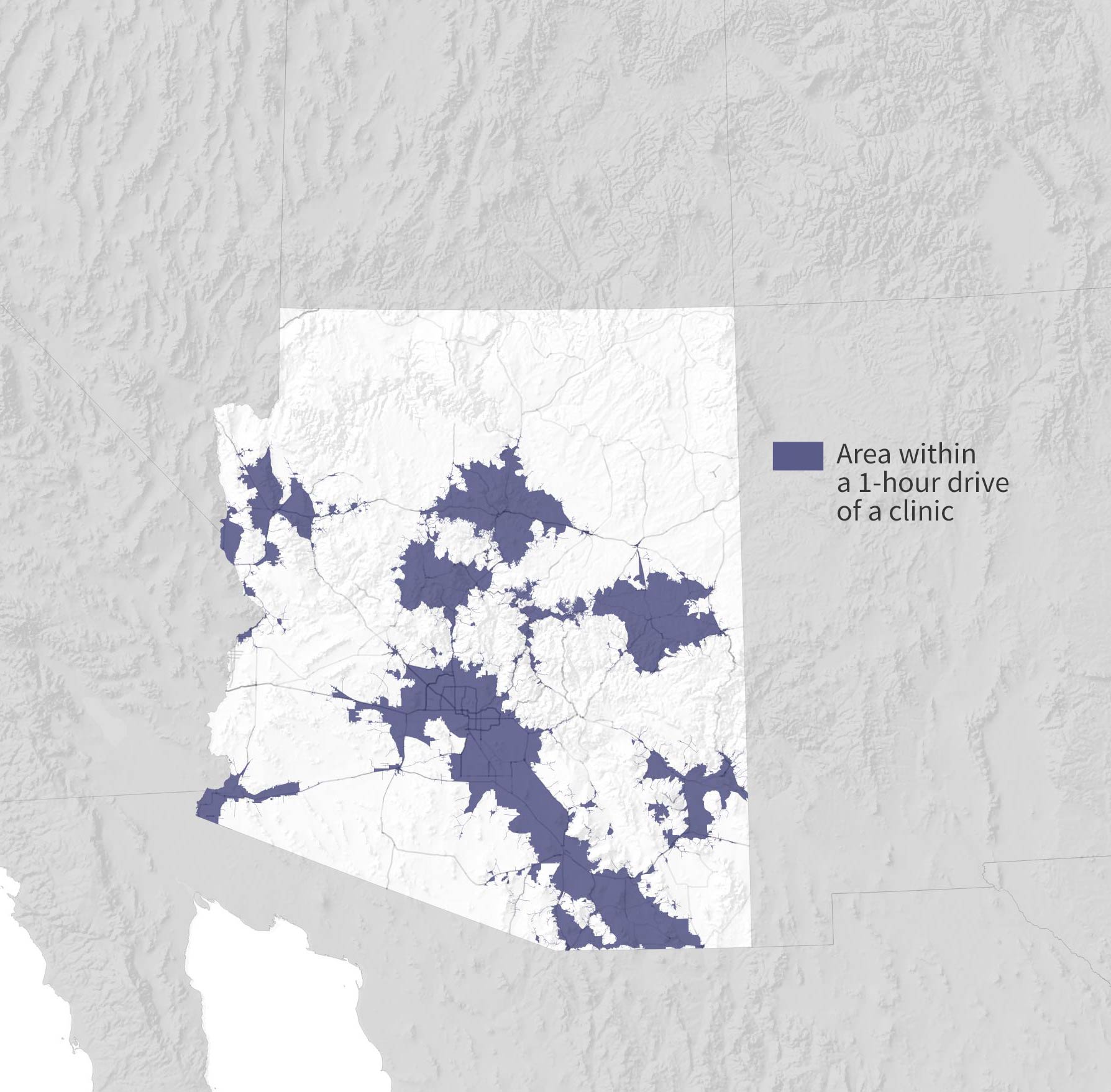

Since 2017, more clinics have opened, expanding access in rural areas with the help of state and federal funding.

Since 2017, more clinics have opened, expanding access in rural areas with the help of state and federal funding.

The opening of these facilities has brought nearly 300,000 adults closer to treatment, according to an AZPM analysis using 2017 census estimates. Note: this number is the general adult population, not the number of people who may need to access treatment for opioid use disorder.

The opening of these facilities has brought nearly 300,000 adults closer to treatment, according to an AZPM analysis using 2017 census estimates. Note: this number is the general adult population, not the number of people who may need to access treatment for opioid use disorder.

Now, more of the state is within a one-hour drive of a clinic. Still, some communities are out of reach.

Now, more of the state is within a one-hour drive of a clinic. Still, some communities are out of reach.

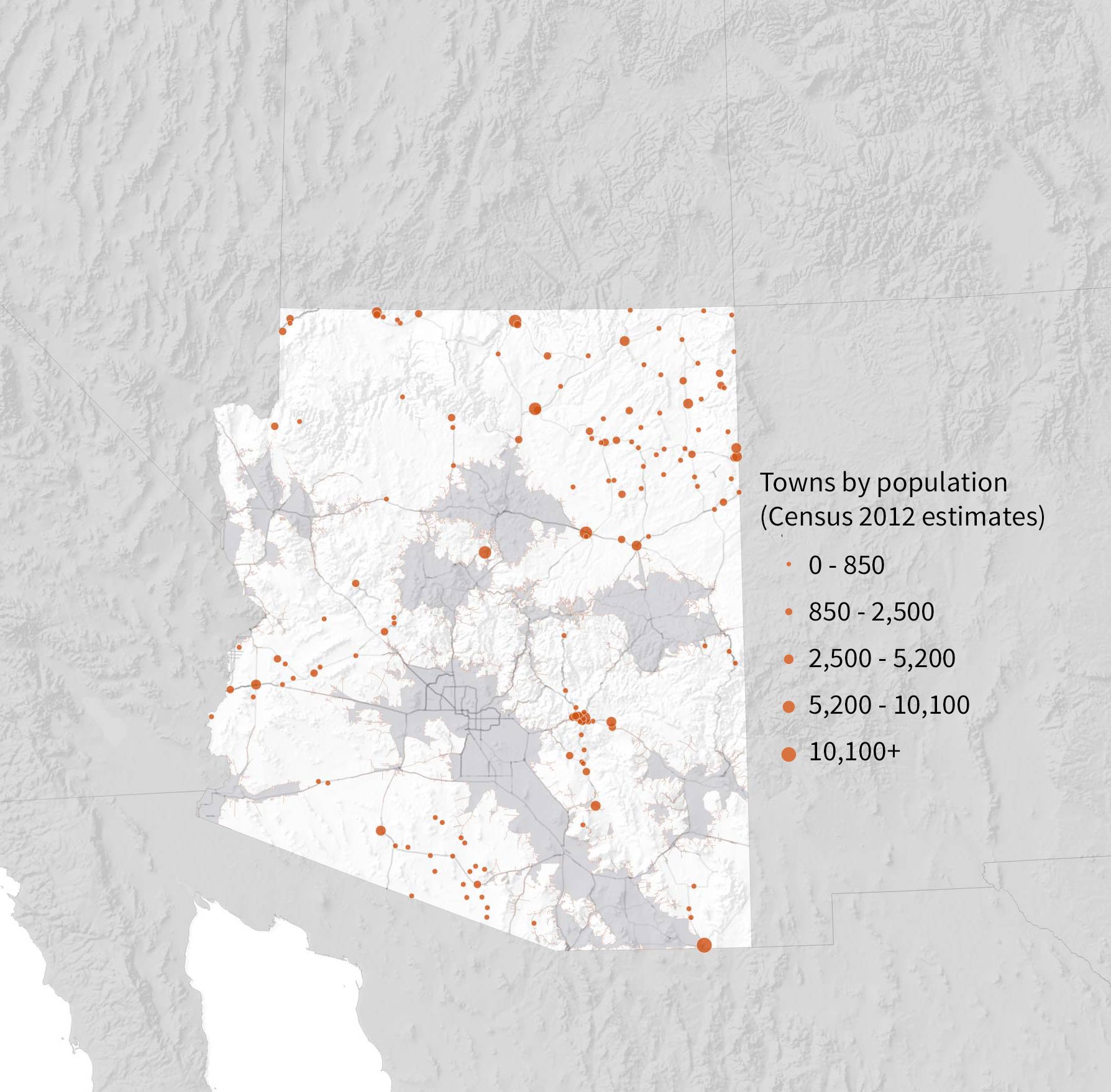

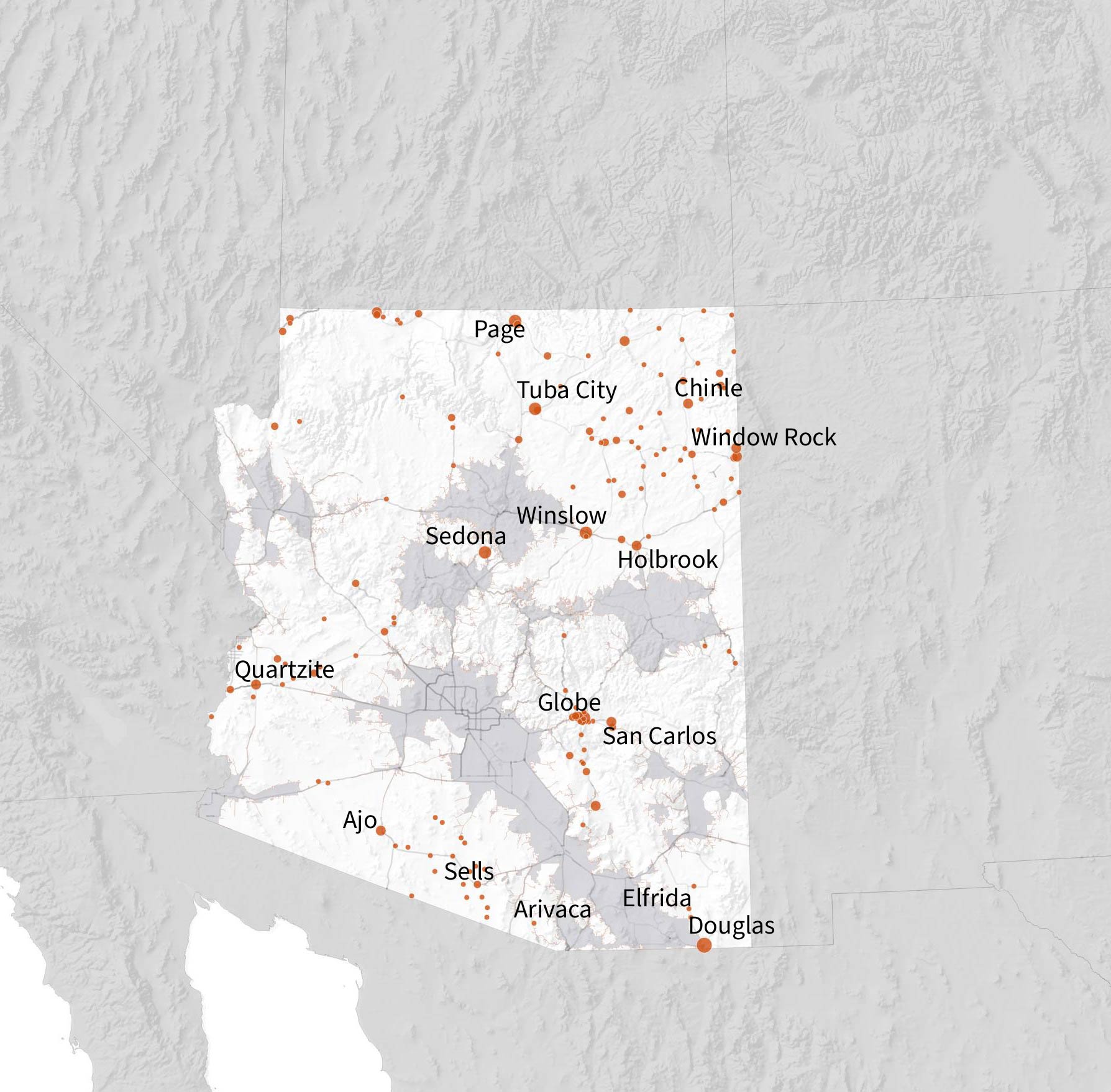

Many smaller towns lie at the edge of, or beyond, a one-hour drive from a treatment clinic.

Many smaller towns lie at the edge of, or beyond, a one-hour drive from a treatment clinic.

Much of the tribal land in Arizona is more than an hour’s drive from a clinic, including the vast majority of the Tohono O’odham and Navajo nations.

Much of the tribal land in Arizona is more than an hour’s drive from a clinic, including the vast majority of the Tohono O’odham and Navajo nations.

The state is trying to enlist local doctors in far-flung communities to prescribe suboxone, which contains buprenorphine, another synthetic opioid. But according to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), adoption has been slow, and many providers prescribing suboxone are in urban areas. And experts say medication isn’t effective without counseling and peer support to go along with it.

For those areas where there aren’t enough potential patients to sustain an entire clinic, the state is weighing its options. Opioid Grants Administrator Hazel Alvarenga said one solution is what’s known as a medication unit, where patients can go daily for the medication paired with telemedicine counseling appointments.

Another option the state is exploring, she said, is transportation hubs that can give isolated patients a ride to the nearest clinic.

Clockwise from top left, Anhelica Gonzalez poses for a portrait outside of the Community Medical Services clinic in Sierra Vista. A vile of methadone at the clinic's dosing station. Suboxone tablets at the clinic's dosing station. Bailey Wilson has scars from heroin usage.

Clockwise from top left, Anhelica Gonzalez poses for a portrait outside of the Community Medical Services clinic in Sierra Vista. A vile of methadone at the clinic's dosing station. Suboxone tablets at the clinic's dosing station. Bailey Wilson has scars from heroin usage.

Stigma remains a potent barrier.

Closing the distance to medication-assisted treatment won’t be enough to help communities with ingrained perceptions about people with addictions as “addicts” or “junkies.”

Bailey Wilson had been addicted to opioids for six years when she enrolled at the Community Medical Services clinic in Sierra Vista last May.

After a stint in detox and subsequent relapse, Wilson, 26, was ready to try something new. She remembers what she thought when a friend told her about methadone.

“I kind of giggled at first. It sounded ridiculous. You know, I’m trying to get off an opioid. I’m not going to trade one addiction for another,” she said.

She now says she feels more secure in her sobriety than at any point since she got out of rehab. But not everybody is aware of methadone’s therapeutic effects. Wilson said that’s made it difficult when trying to find employment, especially when she’s required to take a drug test.

“Unfortunately, the drugs I take every day pop up as opioids,” she said. “People tend to [think], ‘She has a drug problem.’ And they tend to look at that like, ‘She’s kind of a piece of crap.’”

Methadone has been used to treat addiction since the '60s, and it’s always been controversial. For some, treatment can go on indefinitely.

Some consider that replacing one addiction with another.

“I can’t stress enough how false that statement is,” said Chris Anable, a peer support counselor at the Sierra Vista clinic.

Anable said many people still think of addiction as a moral failure — something that can be overcome with willpower and prayer. But modern medicine understands addiction as a disease characterized by relapse.

“A lot of folks will accept the disease concept until it doesn’t suit them, right? Until the addict relapses for the ninth time,” he said.

That’s where medication can help. But in conservative counties like Cochise, Anable said methadone treatment is still considered taboo. Detox facilities rooted in abstinence have been reluctant to collaborate.

“It’s always surprising where that stigma comes from,” he said. “It comes from a lot of the medical folks around. A lot of the nurses and doctors who are misinformed or uneducated about [medication-assisted treatment]. A lot of the law enforcement actually are very supportive of it.”

Cochise County began a deferment program a little more than a year ago, where they’ll offer to bring people in possession of opioids to treatment instead of jail. But for those who do end up in jail, there’s no medication-assisted treatment there — and no system to get people into treatment when they’re released.

At least, no formal system.

“I’ll have the jail call me, give me a heads up. Come by. Scoop 'em up. Get them over here and enroll them in our services,” said Anable.

Peer support counselors are a big reason methadone treatment is successful. Anable struggled with substance abuse for 28 years. He knows what patients are going through.

A big part of his job is recruitment, which means striking up conversation with people holding signs on street corners and leaving his card at trap houses.

He says a history of marginalizing those with addictions coupled with a lack of cooperation between the county’s institutions are the next challenges to address.

Attitudes are changing. Catherine Maddux is the medical care provider at the Cochise County jail. She said she didn’t believe in methadone treatment until she did her research. She now works at the Sierra Vista clinic, prescribing doses for many of the same patients she saw in jail. She’s become a vocal advocate after seeing the difference it made in her patients’ lives.

“If you need it for the rest of your life to go to work every day, have your kids, not use, what’s the difference? You’re not trading one for another, you’re trading a lifestyle that was not very good for a lifestyle that you can actually sustain,” she said.

Maps and analysis by Nick O'Gara and Jake Steinberg. Design by AC Swedbergh. Sources: SAMHSA; ADHS; Census Bureau; Esri; National Map, USGS; Bing Maps/Microsoft.

Eds.: This version of the story corrects the title of Hazel Alvarenga and removes a characterization of the connection between methadone tolerance and duration of treatment.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.