VIEW LARGER A group of 24 people were dropped off this day. These are parents with children only. Solo adults and solo children are likely still in government custody.

VIEW LARGER A group of 24 people were dropped off this day. These are parents with children only. Solo adults and solo children are likely still in government custody. Part of Tracing the Migrant Journey from KJZZ's Fronteras Desk

KJZZ's Fronteras reporting team joined migrants as they traveled thousands of miles to reach the U.S. This multi-part series put reporters on the ground in four countries to document the challenges migrants face on their trek through Central America, Mexico and the U.S. After crossing the U.S.-Mexico border and spending two or three days in government custody, these asylum-seekers have arrived at the Phoenix Welcome Center.

Tracing the Migrant Journey VI

A white bus from the Department of Homeland Security idled in the parking lot of an old school, now a 24/7 shelter. Passengers descended, looked around, and picked up their suitcases and backpacks. Smiling staffers offered to help.

After crossing the U.S.-Mexico border and spending two or three days in government custody, these asylum seekers have arrived at the Phoenix Welcome Center. It’s a new facility run by the International Rescue Committee, a humanitarian group with a chapter in Arizona.

The shelter has hosted over 230 people since opening in July. Staff get told late at night or early in the morning if anyone will be dropped off that day. On a Sunday in late August, 24 asylum seekers arrived, parents with children only. No solo adults, no solo kids.

It’s a brief respite for people before they head elsewhere in the country.

In the main room, a former cafeteria with a large stage, the children headed straight for a small play area, equipped with a play kitchen and other toys. Parents drank coffee at long communal tables.

“Welcome. You are in the Welcome Center of the International Rescue Committee,” supervisor Uriel Gonzalez said. “This is not a detention center. It’s a space that’ll be your home for approximately 24 to 48 hours.”

After the greeting, the first thing people do is ask about charging their phones and the backup batteries for their ankle monitors. They just got them from immigration authorities.

“If it starts to vibrate,” Gonzalez said of the batteries, “it wants to say that it’s losing charge and it’s necessary to change it.”

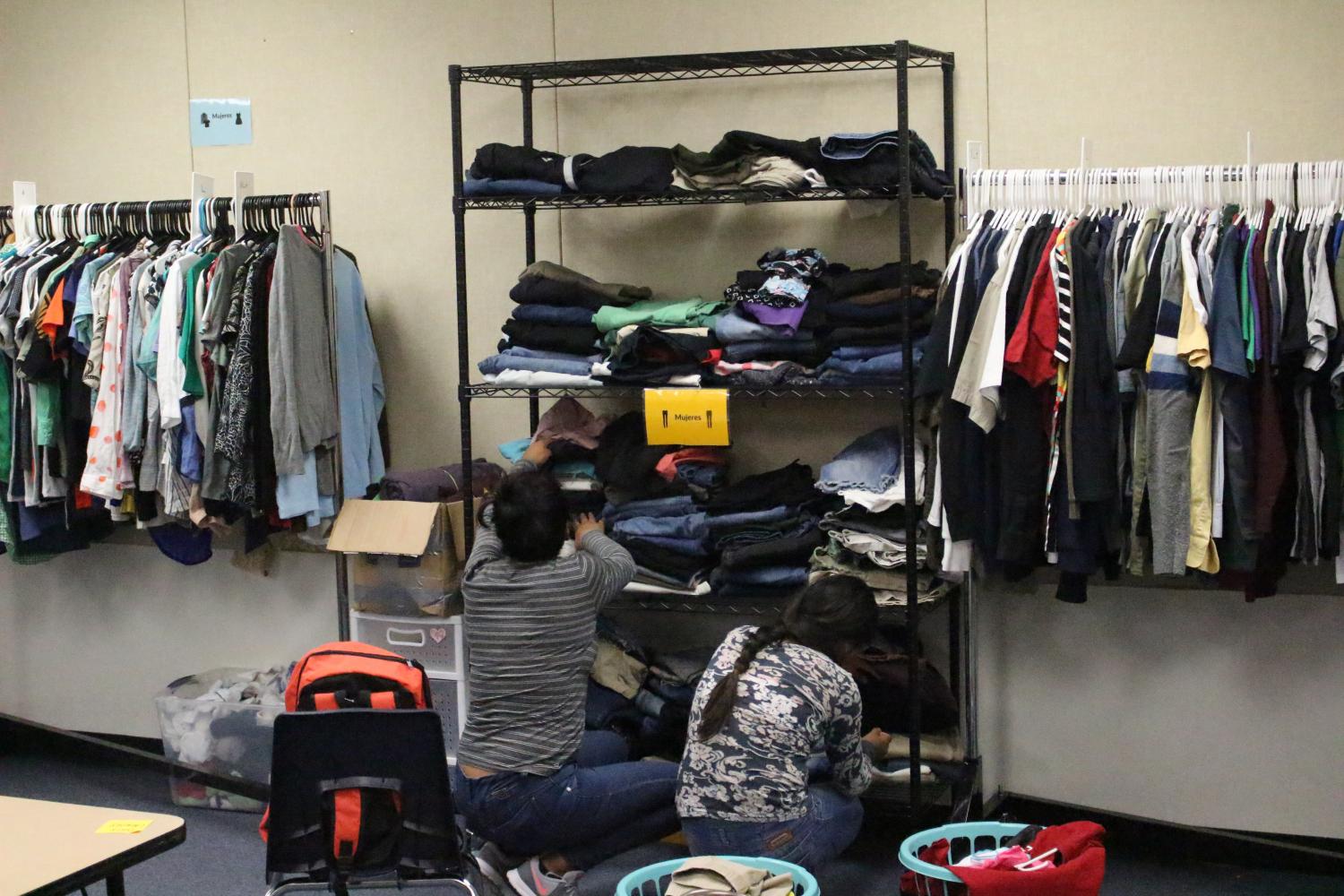

VIEW LARGER In the "Ropa Room," people can select new hygiene products, backpacks and stuffed animals, as well as used clothes and shoes.

VIEW LARGER In the "Ropa Room," people can select new hygiene products, backpacks and stuffed animals, as well as used clothes and shoes. The main room is well-equipped with charging stations.

Next, every family goes through an intake process, where people get lists of legal aid organizations in the cities where they will eventually live. The shelter staff take the names for family members already living in the U.S. Those are the people who will have to book bus or plane tickets for the new arrivals, getting them on their way as soon as possible.

“We make the calls [to the families],” said the IRC’s Nayla Cruz. “We let them know that they’re in Phoenix, where they have to contact to buy the tickets whether it be through a bus station or through the airport. We handle all that after the intake process is done.”

Adults can look in the Ropa Room for donated hygiene products, backpacks, and used clothing and shoes.

Pants, said IRC staffer Niko Valachovic, are hard to come by.

“Pants we tend to wear until they’re out, until we’re not wearing them anymore,” she said. “Also American sizes are way bigger, so it’s hard to find pants that are the right size and the right length.”

The shelter provides medical check-ups, courtesy of One Hundred Angels, and meals from St. Vincent de Paul. The Phoenix Restoration Project has also helped IRC with the shelter.

This shelter is not the only place people go; sometimes migrants stay with local churches. Last spring, the federal government was releasing hundreds of people to the Greyhound bus station. The IRC and its partners soon opened a day shelter at St. Vincent de Paul before securing permits for the Welcome Center.

VIEW LARGER After getting settled and plugging in their phones and ankle monitor batteries, migrants at the IRC shelter go through an intake process.

VIEW LARGER After getting settled and plugging in their phones and ankle monitor batteries, migrants at the IRC shelter go through an intake process. The people who arrived on this day, from Mexico, El Salvador, and Honduras, were generally relieved. Some said the journey was hard, others said they were treated well throughout.

A woman from Honduras — we’re not using her name for safety reasons — fled the country with her 4-year-old son after gangs threatened to kill her if she didn’t sell drugs from her fruit store.

She said there is a lot of organized crime at the U.S.-Mexico border, hoping to kidnap migrants and hold them for ransom. After waiting for about two weeks for the right time, she crossed in the middle of the night. U.S. authorities picked her up.

She spent two nights with the Border Patrol and one with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. On this day, she sat on a red couch at the shelter, waiting for a friend to buy her bus tickets to Dallas. She left two teenage children back home with family.

“I feel sad because I left my children,” she said. “And at the same time happy because I am here, that I will be able to work to send money to them and to my family.”

People continuously leave the shelter for the bus station or airport, as soon as their loved ones can book their travel. Most depart from the Phoenix Greyhound station.

VIEW LARGER Taut, kelly green cots are adorned with blankets, both donated from the American Red Cross.

VIEW LARGER Taut, kelly green cots are adorned with blankets, both donated from the American Red Cross. The migrants who are staying overnight volunteer to sweep, mop, and set up the room for sleeping. Taut, kelly green cots are adorned with blankets, both donated from the American Red Cross.

Over 40,000 family members seeking asylum were dropped off in Phoenix since late last year. According to numbers from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the average daily drop off declined significantly between April and July.

The International Rescue Committee expects the summer heat to keep numbers low for now.

“This is an evolving situation. The numbers that arrive change month to month and immigration policies change,” said spokesman Stanford Prescott. He called the Welcome Center a long-term investment. “We’ll continue to evaluate the decisions here based on the need, but as long as there’s a need here, we’re committed to serving it.”

Once the fall arrives, the IRC will have a better idea of how new immigration policies are affecting people’s decisions to make the migrant journey.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.