Several families of asylum seekers from Guerrero are splitting a few apartments on the border.

Several families of asylum seekers from Guerrero are splitting a few apartments on the border.

Part of Tracing the Migrant Journey from KJZZ's Fronteras Desk

KJZZ's Fronteras reporting team joined migrants as they traveled thousands of miles to reach the U.S. This multipart series put reporters on the ground in four countries to document the challenges migrants face on their trek through Central America, Mexico and the U.S. In San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, the asylum wait list has over 1,100 people. Other border cities have as many, or many more.

Honduras Tecún Umán,

Guatemala Tapachula,

Mexico Guadalajara,

Mexico San Luis Rio Colorado,

Mexico Nogales,

Mexico Yuma,

Arizona Phoenix,

Arizona Portland,

Maine

Tracing the Migrant Journey IV

If you sit with Martin Salgado for more than five minutes, one of several phones he keeps close will eventually ring. Sometimes two ring.

On a recent weekend, his son called right before another call came in.

“I’m not going to hang up. I’m going to answer the other phone. Don’t hang up, don’t hang up!” Salgado told his son.

“Casa de migrantes, buenos días,” he greeted the second caller, an asylum seeker in nearby Mexicali wondering what numbers were being called on the list.

VIEW LARGER A mother and her young daughter from the southern Mexican state of Chiapas wait to cross to ask for asylum.

VIEW LARGER A mother and her young daughter from the southern Mexican state of Chiapas wait to cross to ask for asylum. Salgado, who helps run the Divine Providence shelter, told them the list has been going quickly, and to keep their phones handy.

“I’ve put down that you all are solid, that you’ll come with one call,” he said. “It won’t be much longer.”

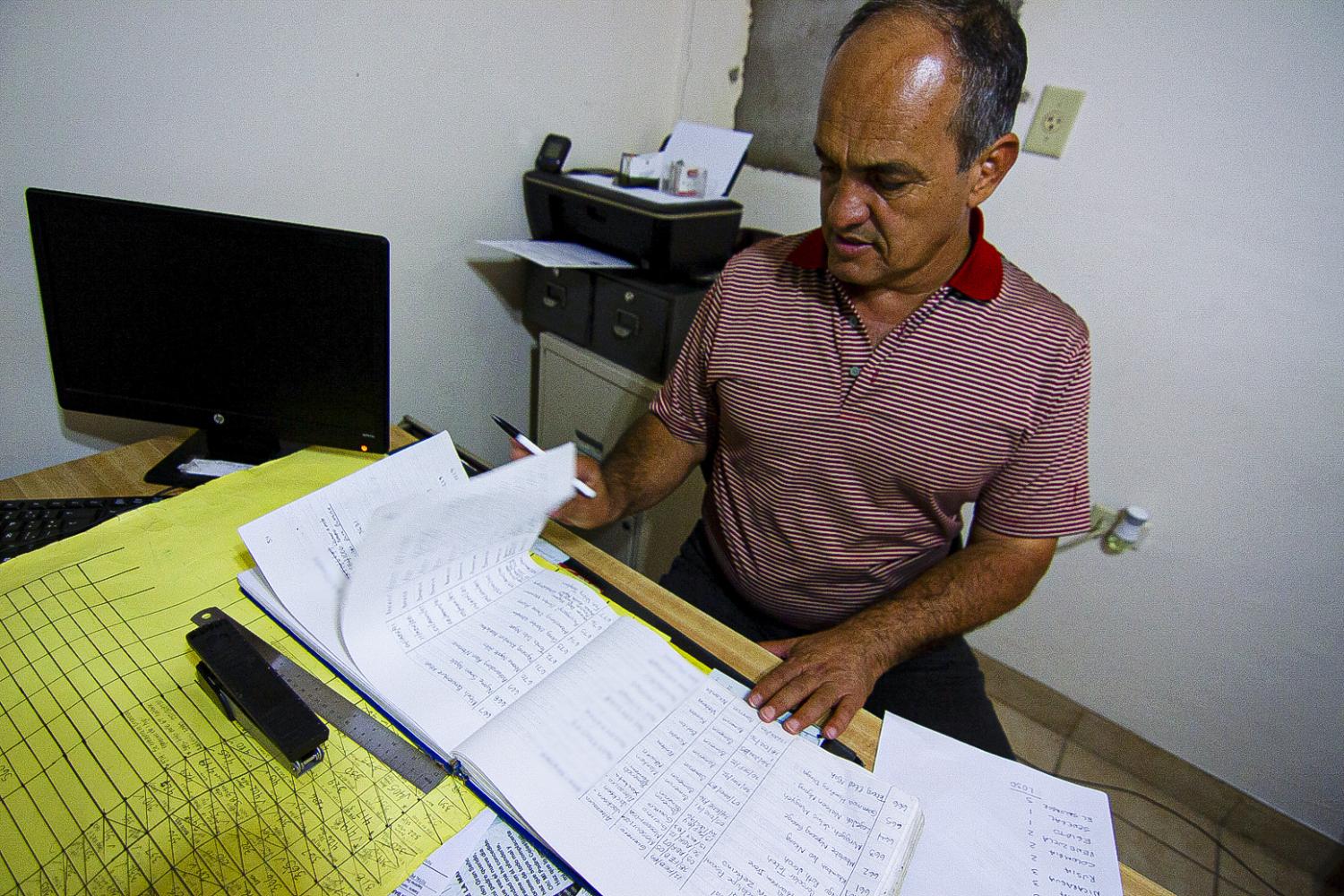

The 85-bed facility — San Luis’ biggest — is the keeper of the asylum list, a huge, handwritten ledger filled with names, arrival dates, nationalities and phone numbers.

This low-tech tool is what determines who gets to cross when to ask for asylum. U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s policy of metering limits the number who can cross daily there to 10 at most.

VIEW LARGER Martin Salgado flips through the asylum wait list. Phone numbers in the image have been blurred.

VIEW LARGER Martin Salgado flips through the asylum wait list. Phone numbers in the image have been blurred. The log now sits at well over 1,100 entries and is filled with people from around the world, not just Central America, according to a mid-August shelter count. Asylum seekers from Cameroon are the second-largest group after Mexicans, who account for over 60% of the total. Honduras is the only Central American country in the top 5.

On a recent weekend, two Ugandans fleeing political and religious persecution arrived with no money and no plan.

“You want to ask asylum to the United States?” Salgado asked them.

“Yeah, we need asylum in the United States of America,” one of them responded.

“The list, the waiting time, to go to the border, to the U.S. border, normally is taking between three to four months,” Salgado informed them.

“Where are we going to stay if we have to wait?” one of the Ugandans responded.

“Yeah, that’s the problem,” the other chimed in.

Those on the list have solved that problem in a number of ways. Some are able to find odd jobs locally and cover rent. Or they head to larger cities like Tijuana for work. Others get a little help.

“We’ve been here for a month, a month and 20 days,” said Ernesto Cano, an asylum seeker from the poor, southern Mexican state of Guerrero.

His family and another have been splitting an impossibly cramped, second-story apartment for about two months. Eight young children and four adults all together. A single mattress was on the floor.

VIEW LARGER Some asylum seekers like these families from Guerrero find cheap apartments while they wait for their numbers to get called

VIEW LARGER Some asylum seekers like these families from Guerrero find cheap apartments while they wait for their numbers to get called Ernesto said they’re being charged around $125 a month for rent, which a brother already in the United States is helping pay. Next door, two more families from Guerrero are similarly sardined, waiting for their numbers to be called.

Adding anxiety to the monotonous waits is the possibility of sudden policy shifts that could shut the door on asylum seekers.

Showing how quickly the ground can shift, a federal judge blocked sweeping asylum restrictions in July only to have a federal appeals court limit the ruling to just two border states the following month. Then in early September that injunction was restored borderwide, only to be reversed by the Supreme Court a few days later.

There’s also the possibility of a safe third-country agreement with Guatemala or other countries that would severely limit the ability of those lists to even ask for asylum. After asking, some may even be sent back to Mexico as their cases proceed through the Remain in Mexico program.

Most get just get three nights at the shelter before they need to move on. But special arrangements are sometimes made. Josefa Contreras and her young son fled Honduras and are staying their long term. In return, she helps out with chores, like dishwashing.

“898,” said Josefa Contreras, referring to her place on the list. “I don’t know how many weeks that will be. It depends on how many people they’re calling daily.”

She has heard rumors of policy shifts, which she described as “troubling,” but said it’s hard to know what’s true, and what it all means for her and her son.

VIEW LARGER Cuban Marco Enrique Sanchez, right, waits with three other asylum seekers to cross and request refuge.

VIEW LARGER Cuban Marco Enrique Sanchez, right, waits with three other asylum seekers to cross and request refuge. “First, trust God,” she said of how she keeps her hopes up amid the uncertainty. “And then think that yes, we’re going to have that opportunity, some day.”

For hundreds in San Luis that day has eventually come. On a recent Saturday, CBP said they could take four people. Cuban Marco Enrique Sanchez’s number was called.

He started his nearly yearlong journey in French Guiana, hoping to reach his ailing father in Las Vegas, and escape the heavy business and free speech limits in Cuba.

“It was pretty difficult for me,” he said. “I crossed like 14 countries to get here.”

That included a week on foot through the tangled, undeveloped jungle between Colombia and Panama known as the Darien Gap, and a five-month wait in San Luis. His father died while he was making his way north.

“Now it’s my turn,” he said, just before he, Salgado and two other asylum seekers hopped in a van and headed to the border. “Thank God.”

Waiting at the border, Salgado made sure everyone had their documents at the ready. And then they walked into the United States, far from sure about what would come next.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.