Train tracks run through Guadalajara. Many migrants use the train, called La Bestia, to travel through Mexico to the U.S. border.

Train tracks run through Guadalajara. Many migrants use the train, called La Bestia, to travel through Mexico to the U.S. border.

Part of Tracing the Migrant Journey from KJZZ's Fronteras Desk

KJZZ's Fronteras reporting team joined migrants as they traveled thousands of miles to reach the U.S. This multipart series put reporters on the ground in four countries to document the challenges migrants face on their trek through Central America, Mexico and the U.S. Here, we pick up the migrant journey in Guadalajara, a major transit point for migrants on their way through Mexico to the United States — but that's been changing.

Tracing the Migrant Journey III

A group of asylum seekers crowds into a large white van outside the FM4 migrant shelter in Guadalajara, Mexico. The door slams shut behind them, and they take off for a local health center. As they weave through city streets, the driver tells them to pay attention.

“Right now, I’d like you to pay attention to the road, because we’re going to go by routes that will help you move through Guadalajara, OK?” Rodrigo González, a social integration specialist with FM4 tells them.

For years, migrant shelters in Guadalajara like FM4 have provided meals, showers and a place to rest for migrants stopping through on their way to the United States.

But that’s changing.

VIEW LARGER A map of the Pacific migrant route through Mexico hangs on a wall in the FM4 migrant shelter in Guadalajara, Mexico.

VIEW LARGER A map of the Pacific migrant route through Mexico hangs on a wall in the FM4 migrant shelter in Guadalajara, Mexico. More and more of their efforts are focused on helping migrants settle into life in Mexico’s second-largest city as a record number of asylum seekers are applying for refuge in Mexico instead of continuing north.

Juan Carlos Fuentes is one of them.

“I decided to stay here,” the 22-year-old from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, said.

Fuentes fled home after a gang in his neighborhood tried to recruit him. He watched as friends who didn’t join started disappearing or showing up dead. Then, he got a call.

“A voice, sharp, hoarse, I don’t know, a diabolical voice, told me ‘Juan Carlos, we know who you are and where you live,’" he said.

The voice said one of his friends had been tortured, killed and left hanging from a bridge. And Fuentes’ fate would be even worse.

He was in shock, he said. But his parents told him he had to leave the country.

“‘I’d rather have to see you through the screen on a telephone than have to visit you in a cemetery.’ Those were my father’s last words to me."

So he left. Hoping to reach family in the United States.

But in February, he asked for asylum at Mexico’s southern border in Tapachula. He said it was too risky to try to get to the U.S. right now.

VIEW LARGER A map of North and Central America on the patio outside the El Refugio migrant shelter in Guadalajara says "Nobody is illegal."

VIEW LARGER A map of North and Central America on the patio outside the El Refugio migrant shelter in Guadalajara says "Nobody is illegal." Seeking refuge in Mexico

A record number of men, women and children have asked for asylum in Mexico this year.

By the end of August, Mexico had received nearly 50,000 asylum applications — the overwhelming majority from Honduras. That’s up from fewer than 30,000 applications in all of 2018. And it's more than 30 times the number of asylum petitions Mexico received just six years ago in 2013.

But the growing number of asylum applications doesn’t mean it’s gotten easier for migrants to stay in Mexico. Many feel stuck.

“It was the only option I had, because immigration got me in southern Mexico,” said David Meléndez, 20, from El Salvador.

Meléndez was studying to be a lawyer before gangs started targeting his family because his dad is a police officer. On top of that, gang members started trying to recruit him, he said, so he had to leave.

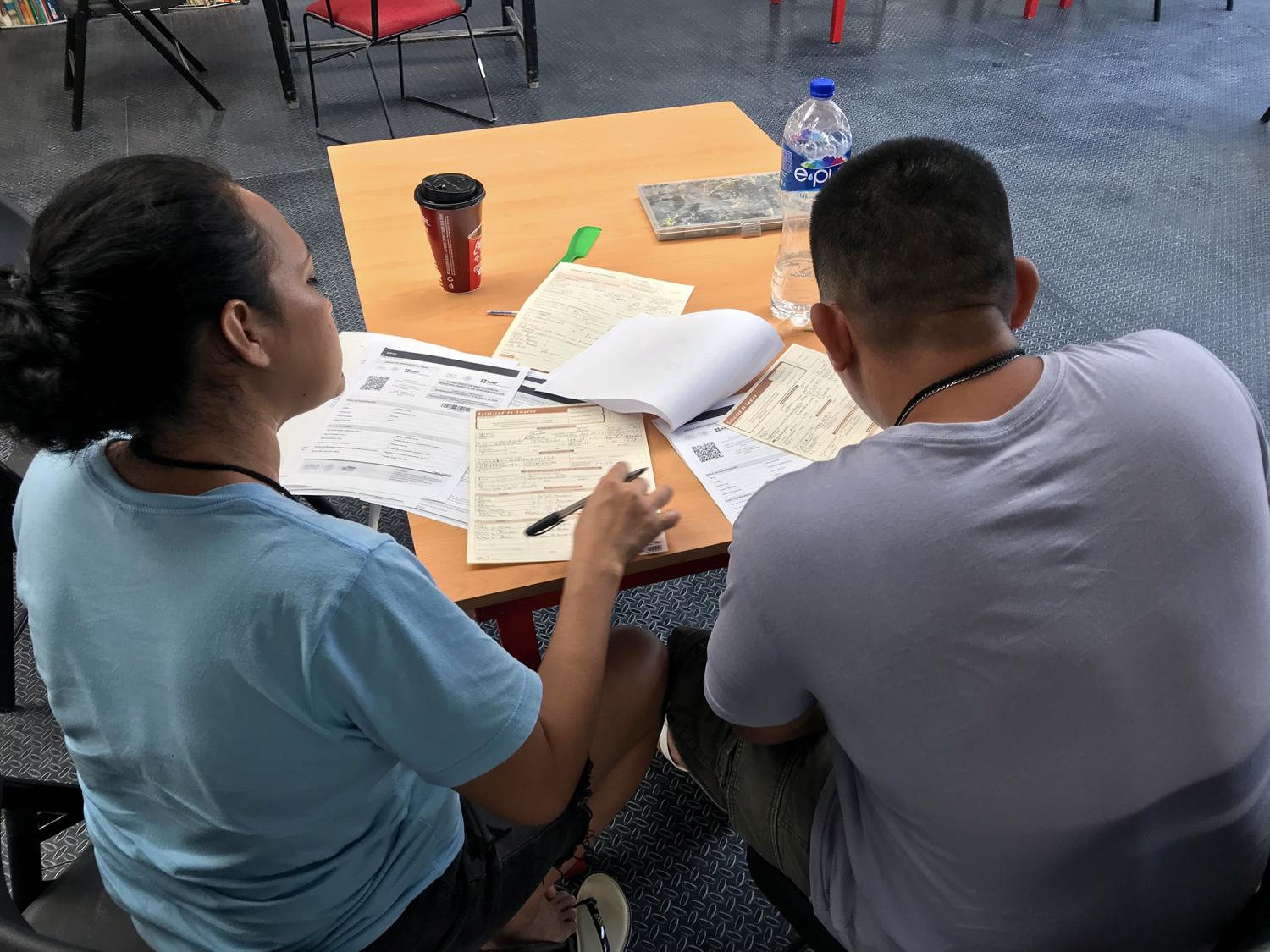

VIEW LARGER Asylum seekers fill out job applications at the FM4 migrant shelter in Guadalajara, Mexico, on Aug. 15, 2019.

VIEW LARGER Asylum seekers fill out job applications at the FM4 migrant shelter in Guadalajara, Mexico, on Aug. 15, 2019. “No one leaves because they want to,” he said, “It’s because we’re forced to. It’s the last option we have left.”

Meléndez said he had planned to ask for asylum in the United States, but when Mexican immigration authorities detained him, he asked for refuge in Mexico instead. He couldn’t risk being deported, he said. If he's sent back home he’ll be killed.

Sitting nearby, his friend Junior Morales shared a similar story.

Like many young men, 20-year-old Morales fled gang recruitment in Honduras. He wants to reach family members living in Kentucky and New York. But he’s asking for asylum in Mexico because amped up immigration enforcement here has made the journey too hard.

“With everything I’ve seen, and heard, it’s a lot more difficult right now,” he said. “It's hard on a person. You see things that you can never erase from your mind.”

Morales has been traveling through Mexico on the cargo train many migrants use to get through the country to the U.S border. He said he’s been assaulted, gone days without food, endured all kinds of weather and seen people fall off the train, their limbs crushed by La Bestia, the beast.

Anti-immigrant sentiments

Traveling through Mexico has always been difficult and dangerous. But many say it’s become a nightmare since Mexico made a deal with the U.S. in June to reduce the number of asylum seekers reaching the northern border. Migrants can’t take buses. There are more checkpoints to avoid. And smugglers are upping their prices.

“People aren’t going to go north anymore,” said Father Alberto Ruiz, who runs the El Refugio migrant shelter on the outskirts of Guadalajara. “There are already people coming back south. And that’s going to go up.”

Shelters at the U.S. border are already saturated with asylum seekers — both those headed north and those the United States has sent back to Mexico to wait for their asylum hearings under the so-called “Remain In Mexico” program.

Ruiz said he’s seeing more and more U.S.-bound asylum seekers coming back to Guadalajara to ask for refuge in Mexico instead.

“And while there are thousands of them, in Mexico we’re millions of people,” he said. “We could absorb these asylum seekers easily if there was a will. But not with an anti-immigrant mentality.”

VIEW LARGER Father Alberto Ruiz (left) makes calls to help an asylum seeker find a job.

VIEW LARGER Father Alberto Ruiz (left) makes calls to help an asylum seeker find a job. Ruiz said Mexico has the capacity to provide refuge for asylum seekers. But growing push-back against migrants has made life hard for those who stay.

“The truth is, there’s a lot of discrimination against migrants here, and exploitation,” said Mario Rios, a 39-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador.

Like most waiting for their asylum cases to be processed, Rios doesn’t have a legal work permit. Employers take advantage of that.

But it’s still better than the alternative, he said.

“Everybody already know about the president in the United States right now, and the laws he’s put in place to keep migrants out,” he said.

Rios is afraid if he tries to enter the United States, he’ll be locked up in a detention center. Or worse, deported back to the violence he left at home.

That’s a risk he can’t take.

Making a life

Sitting at a wooden table in the FM4 migrant shelter, Juan Carlos Fuentes, from Honduras, listened as La Bestia rolled by, the piercing train whistle rattling through the echoey room.

He said he’s hopeful he can build a dignified life in Mexico. But he’s scared, too.

“I had to abandon all of my family when I left,” he said. “Now I’m alone in a place where I don’t know anyone.”

That isolation makes migrants vulnerable, says María José Lazcano, the shelter’s outreach coordinator.

VIEW LARGER Clothes and sheets sway on the clothesline at the El Refugio migrant shelter in Guadalajara.

VIEW LARGER Clothes and sheets sway on the clothesline at the El Refugio migrant shelter in Guadalajara. “In Mexico, for a lot of them it’s start from scratch, from nothing,” she said. “They’re not just going to the United States because of the American dream or whatever, but also sometimes because they have family there, so it’s a matter of family reunification. Or they’ve already lived there and have networks and friends.”

She said as Mexico and the U.S. crack down on migrants reaching the U.S. border, it’s creating more dangerous situations for migrants who end up being forced to stay in Mexico. Not only does it separate them from connections north of the border, but they have to take more dangerous routes through Mexico to avoid being detained by authorities. That often leave them exposed to organized crime.

“So it make[s] no sense that if they went through everything that they went through to get here, that they will end up living in the exact same conditions that they were living in their countries," she said.

Fuentes is grateful for the safety he’s felt in Mexico after fleeing gangs back home. But it's hard to be alone, and he can’t go home. His hope is that he'll be able to reach his family in the U.S. someday.

“Truthfully, if the opportunity came along to get to the United States, I’d take it without even thinking about it," Fuentes said.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.